2.picc.2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.2.2.0-timp.perc(2):cowbell/xyl/BD/chimes/glsp/vib-harp-pft.cel-strings

This work requires additional technological components and/or amplification.

NOTE: Due to certain balance issues in the orchestration, it is strongly recommended that very light amplification of the solo quartet be used with the sound controlled through a mixing board located at the rear, behind the audience.

Abbreviations (PDF)

Boosey & Hawkes (Hendon Music)

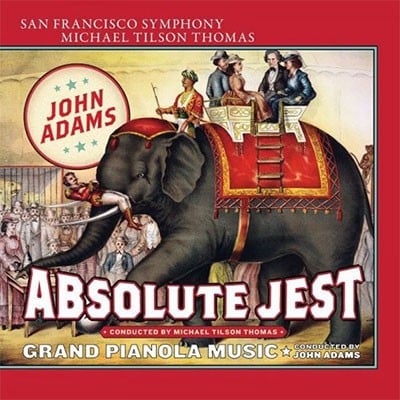

More than three decades have passed since the San Francisco Symphony gave its first world premiere of music by John Adams (the choral-orchestral Harmonium in 1981). The event marked the beginning of a longstanding relationship between composer and orchestra that has resulted in the commissioning of several landmark works: Adams’s breakthrough orchestral composition, Harmonielehre (a new recording of which has just been released), El Dorado, the millennial “nativity oratorio” El Niño, the opera A Flowering Tree, and My Father Knew Charles Ives.

Readers of Adams’s blog, “Hell Mouth,” can find observations equally entertaining and insightful about the fate of the composer in today’s cultural climate. In one entry, for example, he muses about the times when his pieces have been programmed alongside Beethoven: “Another rite of passage that one must endure, if you’re to be a ‘classical’ composer, is to share the bed with one of the large guys.” In fact, that milestone first San Francisco Symphony premiere of Adams’s music was followed by an account of the Emperor Concerto. “I think none of us,” program annotator Michael Steinberg later wrote, “had anticipated how those concerts would stick in our memories primarily as the ones at which we first heard Harmonium.”

In Absolute Jest, commissioned to mark the Symphony’s centennial season, Adams explores how his own affinity for Beethoven leads down surprising new creative paths. “I frequently have these powerful, archetypal experiences with Beethoven,” says Adams, “but with the piano sonatas and the quartets, which for me are the most vivid, rather than with the symphonies and the public music that gets heard all the time.” Comprising a large, widely spanning single movement, Absolute Jest incorporates more than a half dozen Beethoven fragments, mostly from the late string quartets. These fragments, however, are not simply rearranged “quotations” but provide the raw material for a score that could be by none other than John Adams.

The unifying factor here is the composer’s attraction to what he calls “the ecstatic energy of Beethoven.” Ever since Shaker Loops, a seminal work from 1978 that evolved from his first foray into the string quartet (Wavemaker), the Adams style has featured as one of its signature components an irresistibly powerful sense of momentum. This momentum is driven both by energetic pulsation and by an architectural grasp of tonal gravitation—traits that find their paradigmatic expression in Beethoven. Even more, points out Adams—while voicing caution against the temptation to construe the art of the past as if it mirrored only present-day perspectives—Beethoven “was the master of taking the minimal amount of information and turning it into fantastic, expressive, and energized structures.” He compares what Beethoven achieved with the Fifth Symphony’s famous four-note motto or, in his late period, with the expanded universe that he built from a banal waltz tune in the Diabelli Variations, to “atomic theory” in action and to the construction of complex compounds out of basic molecules.

But it was a later composer who provided the catalyst for the underlying concept of Absolute Jest. Around the time Adams was beginning to think of the new commission, he attended a performance by MTT and the Symphony of Stravinsky’s Pulcinella Suite, derived from the 1920 ballet score in which the composer recycled eighteenth-century source material. What especially struck Adams was “the fact that Stravinsky could take fragments from music more than 200 years old and preserve some aspects of the original form but make a Stravinsky piece.”

In contrast to Stravinsky, who “updated” whole swathes of previously composed material in Pulcinella, Adams restricts himself in Absolute Jest to using brief, isolated, and originally unrelated fragments. These he uses as building blocks to construct a single movement of large proportions. Adams discovered after he had composed the score that along with his obviously conscious choice of sources, some unexpected or subconscious Beethovenian allusions and models seemed to become part of the process as well. “You have to be careful not to think of these things while composing,” he remarks. “Otherwise it’s like staring into the sun.”

Yet instead of producing an instance of the “anxiety of influence”—literary critic Harold Bloom’s famous term for the creative pressure exerted by past achievements—the prospect of using fragments directly from Beethoven seems to have had a remarkably liberating effect. To Adams’s metaphors from physics and chemistry one is tempted to add another from microbiology. Absolute Jest involves the recombination and transfer of musical DNA to create something with distinctively new properties. “I think probably more than any other piece of mine,” says Adams, “this one is about invention in the sense of taking material and doing all kinds of things with it.”

Most of the Beethoven fragments in Absolute Jest originate from scherzos from the composer’s late period: in particular, the scherzos of the String Quartets in C-sharp minor, Opus 131, and F major, Opus 135. Indeed, Beethoven’s genius for unleashing unsuspected power from “minimal information” is especially pronounced in his scherzos. Here, as in the Diabelli Variations, he uses unpromisingly elementary musical impulses—take the three-note rhythmic cell thundered by the timpani in the Ninth Symphony’s scherzo—as the seeds of immensely inventive movements. By the same token, Beethoven’s own label for these movements—scherzo or “joke”—suggests the irony of such rough magic, by which the trivial is transformed into something cosmic and profound. Adams seems to explore this connection further by juxtaposing his scherzo fragments with others from the “serious” opening fugue of Opus 131 as well as with a brief bit of the imposing Grosse Fuge (“Great Fugue”), originally written as the finale to the Quartet in B-flat, Opus 130.

Adams also includes a winking reference to Beethoven’s “public” music by setting Absolute Jest into motion with the rhythmic motif from the Ninth just mentioned, initially given as a telegraphic pulse played by the timpani on a single pitch. (Adams aficionados will note that Son of Chamber Symphony, his recent “second-generation” play on the Schoenberg-glossing Chamber Symphony of 1992, also alludes to the Ninth scherzo, but in an altogether different way.) That motif’s immediately recognizable octave leap, later spelled out in slightly varied rhythms by diverse instruments, is characteristically recombined with other fragments as the music unfolds.

Soon after that opening gesture, Adams introduces a sonority completely foreign to Beethoven: the piquant “tintinnabulation” (as the composer terms it) of cowbells, harp, and piano all tuned in a special way (mean intonation as opposed to the standard Western tuning used for the rest of the ensemble). This “alternative” tuning has its own rich history among such West Coast maverick composers as Harry Partch and Lou Harrison. Adams himself notes that he became enamored of its possibility when he used it for The Dharma at Big Sur, his concerto for electric violin from 2003. Throughout, this trio of mean-tuned instruments functions as a “consort in the medieval sense.”

Another unusual feature of Absolute Jest’s scoring is the presence of a solo string quartet that weaves in and out of the larger fabric created by Adams’s large orchestra. The challenge posed by this remarkable choice of instrumentation further widens the scope of his invention. Although Adams had been immersed in Beethoven’s string quartets while conceiving the piece, it was through his collaboration with the St. Lawrence Quartet (for whom he composed his substantial String Quartet in 2008) that the idea of combining string quartet and orchestra occurred to him—“a repertory black hole,” as the composer jokes.

In terms of its form, Adams suggests that Absolute Jest is “the closest thing I’ve written to variations—although in this case there is no single tune as in a classic set of variations like Bach’s Goldberg Variations.” The opening minutes percolate with a sense of expectation as fragments from the scherzos of the Ninth and the C-sharp minor Quartet, Opus 131, flash across the landscape. Shifts in tempo and texture are wonderfully effected and never predictable, leading to a lengthy meditation on ideas from the irrepressibly energetic Opus 135 scherzo (Beethoven’s final quartet and last major composition), with the solo quartet now and again taking the spotlight. A marked change of atmosphere arrives with a haunting section in which Adams crafts an entirely new fugal passage from fragments of the opening of Opus 131 as well as from the quasi-atonal strain and pull of the Grosse Fuge. Indeed, a newfound fascination with age-old countrapuntal techniques is a hallmark of Absolute Jest. In some passages, simultaneous statements of the same material are parsed into varying durations to create an effect of multiple layerings of time.

Yet another significant fragment comes from earlier Beethoven: the Waldstein Piano Sonata in C major, Opus 53. Adams recalls listening from the other room while his son Sam—himself a composer whose work has been commissioned by MTT and the Symphony for next season—was practicing the Beethoven sonata as a teenager: “Even after hearing him play it over and over, I never got tired of hearing him practice it and became fascinated by the opening bars.” He worked his fascination with this middle-period sonata into Absolute Jest’s highly dramatic coda, which “rides upon the harmonic changes at the opening of the Waldstein.”

Tonality itself emerges as an intriguing subplot alongside the continual morphing and recombining of the Beethoven fragments. In the process Adams weaves in references to his own body of work, from the rolling, Emperor-style waves of E-flat major to which he once alluded in his “tricksterish” Grand Pianola Music (1982) to the rousing energies (à la Shaker Loops) that gather power in the coda. But no sooner do these coalesce and resolve into a powerfully anchored tonal goal of B-flat than the music dissolves for a final, enigmatic comment from the “detuned” percussion consort.

— Thomas May

Reproduction Rights:

Thomas May is the editor of The John Adams Reader. This note originally appeared in the program book of the San Francisco Symphony and is used by permission.

Copyright © 2012 San Francisco Symphony. Permission to reprint required

John Adams’s energetic scherzo for string quartet and orchestra draws on fragments from Beethoven’s Op. 131 and Op. 135 string quartets and Große Fuge. The composer was particularly attracted to “the ecstatic energy of Beethoven” and how he “was the master of taking the minimal amount of information and turning it into fantastic, expressive, and energized structures.” As Musical America noted: “Dense, roiling, and furiously inventive, Absolute Jest emerges as a gripping 25-minute sonic joy ride … You can hear the echoes of Beethoven throughout the piece—chopped, remixed, inside out and upside down, redistributed to the string quartet and throughout the orchestra—and you can almost see the composer smiling at the results.” The work has become one of Adams’s most popular works with over 150 performances worldwide since its premiere.

“Absolute Jest may well be the finest concerto for string quartet and orchestra ever written.”

— Lawrence A. Johnson, Chicago Classical Review

“Absolute Jest is a work of terrific imagination and out-of-the-gate energy…”

— Richard Scheinin, San Jose Mercury News

“Adams’ single-movement opus for string quartet and orchestra [Absolute Jest] is an audacious and affectionate riff on Beethoven’s scherzos. Dense, roiling and furiously inventive, it emerges as a gripping 25-minute sonic joy ride.”

— Georgia Rowe, Musical America

“The wedding between string quartet and orchestra was masterly…a significant addition to the increasingly impressive Adams canon.”

— David Littlejohn, Wall Street Journal

St. Lawrence String Quartet / San Francisco Symphony / Michael Tilson Thomas

(c) 2015 San Francisco Symphony

SFS Media: SFS 0063