3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.4.3.0-timp.perc:xyl/3tom-t/cast-

harp-mandolin-pft-strings

Abbreviations (PDF)

Boosey & Hawkes

Thanks to Balanchine, Agon is by far the best-known of Stravinsky's non-tonal works. A distillation of rhythmic energies, of dance gestures, of deft instrumentation (with prominent parts for mandolin, harp, timpani, and castanets), it is a plotless ballet whose long gestation accounts for its exceptional range of tonal and serial ingredients.

Repertoire note by Joseph Horowitz

Agon joined Apollo and Orpheus as the final work in a trilogy of Greek-inspired ballets Stravinsky made in close collaboration with Balanchine. Agon, however, has no scenario: it is entirely abstract. Its stylised structure and formal language are more a meditation on the idea of dance, and on the idea of Greek myth as contest, game or struggle (the meaning of the Greek title). It plays with the number 12: there are 12 dancers; there are essentially 12 dances (excluding the instrumental Prelude and Interludes, which punctuate the structure); and it also contains aspects of Stravinsky’s own interpretation of the 12-note (serial) compositional method. If this all sounds coldly mathematical, then the exuberant playfulness of the music will come as a great surprise! It works equally well in the concert hall as on the ballet stage. Pierre Boulez would often conduct Agon as part of programmes of later 20th-century modernist music. It could be coupled with such works as Birtwistle’s In Broken Images or Andriessen’s Agamemnon, or even Boulez’s own Le Marteau sans maître.

Repertoire note by Jonathan Cross

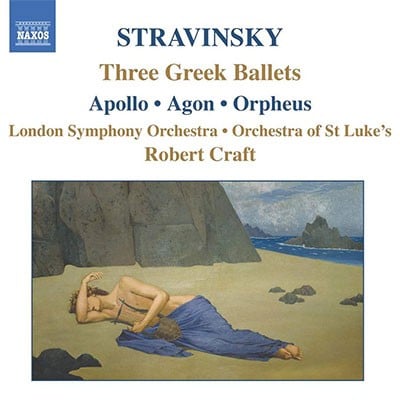

Orchestra of St Luke's/Robert Craft

Naxos 8.557502