Bote & Bock

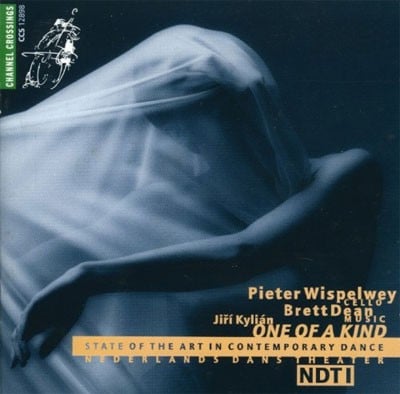

As part of the celebrations on May 5th of the 150th anniversary of the Dutch Constitution, the Home Affairs Minister Hans Dijkstal requested that Jirí Kylián base his piece on Article 1 of the document: All in the Netherlands are in equal circumstances to be treated equally. Discrimination on the grounds of religion, conviction, political leanings, race, sex or on any other grounds, is not permitted.

This article, the principle of liberty, was part of the inspiration for One of a Kind. Apart from being one of the cornerstones of Dutch society, liberty is a concept which raises a number of questions. What is true liberty? To what extent does individual liberty affect the liberty of others? Is liberty the estate of human beings only? In this article the Constitution represents the consciousness in every Dutch citizen of enforcing as well as defending liberty.

A female dancer rises from the crowd and joins in the scenes taking place on the stage. She represents the audience in the spectacle being witnessed. She is our common liberty, our common conscious. Eventually she returns to the audience and becomes a part of it. Has anything changed? Have we improved, become more aware of our own being and that of others?

This production has been made possible by a financial contribution from the Ministry of Home Affairs in connection with the celebration of the 150th anniversary of the Dutch Constitution.

Madrigals by Gesualdo, chanting Tibetan monks, Inuit vocal games and Pieter Wispelwey's cello: these are the main elements of this musical journey. I as asked to join the project relatively late in the day, at a time when Jirí Kyliáns concept of the sounds he wanted was already well advanced and delightfully idiosyncratic. He had collected a veritable archive of aural phenomena which had fascinated him for years. So we added some African drums, contemporary choral techniques and various examples of Australian bird song. But what kind of a journey were we embarking upon? The initial guidelines from the choreographer suggested a life cycle scenario, divided accordingly into three acts. That was the starting point, and I just took it from there.

Act One

The piece starts with the sounds of harmonic singing, as found in the Hoomi tradition of Mongolia, and Tibetan overtone chanting. These ethereal voices open a window onto an evolving soundscape in which other elements discover their place. Ceremonial bells and crotales, dreamy string flageolets, a guttural droning of voice and cello, the squeaky pendulum of a playground swing, and a breathy Inuit katajjaq, or throat song-game. These elements are driven relentlessly forward by basses and cellos to reach a dynamic peak. Out of the resultant 'rubble' finally emerges the lone elegant cello of Pieter Wispelwey. He announces single phrases that we can only later piece together as fragments of Sparge la morte from Carlo Gesualdo's fourth book of madrigals. The path leading to the madrigal itself (ponticello strings, percussion) is shrouded in mystery, much like the scant details of Gesualdo's own bizarre life.

Carlo, the infamous, troubled Prince of Venosa, who murdered his own wife and her lover in Naples in 1594, is a figure that plays an integral part in the unfolding musical drama. His duplicity of lyricism and threat will accompany us throughout the various stages of the piece. ( ... but rest assured, he doesn't kill anybody in this show!) Sparge la morte works its precarious charm upon us, and the cellist replies with his very own 'madrigal': a soliloquy that soars to the instrument's highest register.

Act Two

We slowly awake out of the calm of the cello solo. At first, life's birth and initial growth seem more like some 'Nibelungen' dawn. But the horns we hear are no mistaken doorway into 'Das Rheingold'! These horns herald a dance of hedonistic earthiness. Naturally, the cellist has his own view of this dynamism and enters setting an even faster course, pursued and then consoled by the consort of Gesualdo singers.

The dance proceeds through various pizzicato and tremolo variants, then stops abruptly, leaving a carpet of high voices. When the rhythmic forces try to reenter the scene, they are unable to regain their initial vigor. Everything turns quiet. Then the cello, accompanied sporadically by a viola, joins in dialogue with some Australian pied butcher birds. Their 'songs of nature' reawaken the spirits of movement and vitality, and the music tumbles once again into action, even agitation ... The quickening step of African drums steers us towards a menacing darkness as the cello's driving motor returns. A chase ensues. Finally, all energy is spent and an uneasy calm reigns.

Act Three

The first time I met with Jirí Kylián to discuss this production, he showed me photos of Atsushi Kitagawara's sensational set designs. The image of strands of brilliant white light from stage to ceiling in the 3rd Act left a strong impression, awakening ideas of the afterlife-eternity-transfiguration variety. Ever since that first meeting, I knew we had to create a very particular sound for the opening of this act, a crystalline brightness coming from many cellos, something both shimmering and intense. The celloscape that evolves out of this multitude of harmonics is enhanced by bells and an intriguing percussion instrument called a waterphone. But after so much light, it's also nice to sit in the shade for a while. Low, sombre cellos murmur briefly before the dark foreboding of Gesualdo returns. The opening bars of his tortured madrigal Moro lasso transport us unexpectedly back in time. The ensemble of deep cellos replies to each successive vocal entrance with increasing intensity, pushing the sound towards the upper stratosphere where the act began. The fuller exploration of Gesualdo's harmonies that ensues (in the form of a collage based on the Moro lasso motive) brings the music back to a floating stillness. Then, even the short rhythmic section that interrupts this state of repose with its Inuit reminiscences and metallic pulse, cannot substantially shake the music of its resolve to remain calm, composed and spacious. It is this atmosphere which gives shape to the work's last moment of focus and concentration: the poignant Lamento from Benjamin Britten's 1st Cello Suite.

Brett Dean

"... a fascinating work with a strong coherence." (De Telegraaf, 30 Apr 1998)

"... very expressive: the cellist haunts, reacts, taps, makes sounds like breaking icicles, he blows sound bubbles that explode. This rich landscape of sounds is determining the dance; rhythm and dynamics are directing the movements." (De Volkskrant, 07 May 1998)

"A storm of music rages across the stage. This is sparkling, dance and music compete for superiority." (Trouw, 07 May 1998)

Pieter Wispelwey / Brett Dean / Simon Hunt / Michael Askill / Stefan de Leval Jezierski / Members of the Nederlands Kamerkoor / RIAS Kammerchor (Berlin) / Brett Dean cond.

Channel Crossings CCS 12898