Robin Holloway: interview on Fifth Concerto for Orchestra

Robin Holloway discusses how his Fifth Concerto for Orchestra, receiving its premiere at the BBC Proms on 4 August, seeks to combine constructivism with virtuosity.

You’ve exhaustively studied orchestral music across the centuries. Who are your heroes?

There are great orchestrators across a bewildering range of styles. To take two polar examples, Stravinsky is unambiguously hard-edged whereas Debussy is veiled and full of suggestion. And Richard Strauss is an orchestral master totally unlike either, who finds a technique to perfectly suit his style, just as Bruckner does for his own world. The absolutely infallible orchestrators are Mahler and Ravel, and I greatly admire Britten for his exceptional clarity. Just as interesting are those composers who are examples of how not to orchestrate, yet achieve a totally personal idiom: any other sound would be inappropriate. And there are many byways — lovely or exciting orchestral discoveries in countless composers that give pleasure, instruction, example.

When does an orchestral piece become a concerto for orchestra?

It is the emphasis on display and prowess that defines a concerto for orchestra and makes it unlike a symphony in form and content. There are no givens, so it appeals to me as a very ‘open’ genre. Despite their very different starting points and aims, all five of my concertos relish the multiple opportunities for virtuosity: showpiece sections for the orchestra as a whole, passages that focus on family sections, and solos where the individuals can emerge and shine.

Can orchestral showmanship and compositional argument sit comfortably together?

Yes, absolutely. You just have to think of pieces like Daphnis and Chloë, Jeux or The Rite of Spring. Virtuosity is an intrinsic part of the music but this does not demean the greatness of the work. Even a score like Bolero can be viewed as a concerto for orchestra. When Ravel notoriously said it was an orchestral work without music he was uttering a provocation, but we can view it now in a chain of works defining new orchestral forms culminating in Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra.

Your Fourth Concerto was described by the San Francisco Chronicle as “huge and splendiferous”. Yet the Fifth is compact in scale.

Yes. After the epic Fourth I wanted to do something different, so was pleased when the BBC Radio 3 commission for the Fifth was humorously firm that it “should not be long”. I was also writing a series of miniatures, the Five Temperaments for wind quintet and Six Quartettini for string quartet, so was exploring compact forms which might be thought to be ‘against type’. One model for the Fifth Concerto was Schoenberg’s Five Orchestral Pieces, a large work in a short duration that had the intensity I was seeking.

The Fifth returns to the density of your earlier concertos. Why is this?

Its composition followed a revisiting of my First Concerto, to renotate the earlier movements and revise the later movements. I was rediscovering my young self of nearly half a century ago when I was a total constructivist and raving expressionist; something of both is recaptured in the concentration of the Fifth Concerto, though obviously the experience and range of expression are much wider. The scale demanded there should be no sprawl, so rather like Manhattan the only solution was to build upwards.

Inspiration for your concertos has ranged from memories of travel to medieval epic poetry. Is this concerto as abstract as it appears?

Yes, it is. It neither tells stories nor depicts places or events. The only pre-compositional triggers I remember were a couple of intense colour experiences. One was walking across one of those Cambridge lawns that have been so lovingly tended down the ages. The grass was sumptuous and velvety and the light was skimming: the sensation was of swimming through green. The other was sitting on a bus in a traffic jam and fixing my eyes onto a newly-painted pillar post box in the sunlight, astounded at the visual thrill of the brilliant red. This prompted the idea of coloristic ideas for each of the five movements, not in the literal heraldic manner of Bliss’s Colour Symphony but in a more sensory way.

How did the Fifth Concerto evolve?

It grew organically from nuclei, which initially had no thematic basis. They were ideas of texture, sound and character before any pitches were defined. The first movement starts from a total blackness of mood and spirit, moving through a dense chord sequence whose elaborate decoration fills the total chromatic and entire orchestral space. The second movement, with its springing momentum and buoyant airiness, provides the complete antithesis. The remaining three movements occupy the space between the extremes, the last attempting a synthesis of all these elements through a flowing lyricism akin to the last of Schoenberg’s Five Orchestral Pieces. My aim was to achieve from the polyphonic density a totally expressive dissonant luminosity.

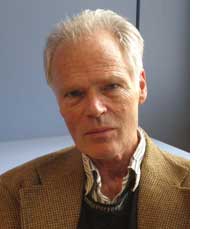

Robin Holloway

Fifth Concerto for Orchestra (2009-10) 25’

4 August 2011 (world premiere)

BBC Proms, Royal Albert Hall, London

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Donald Runnicles

> For further information visit the BBC Proms website.

> Further information on Work: Fifth Concerto for Orchestra

Photo: Pippa Patterson