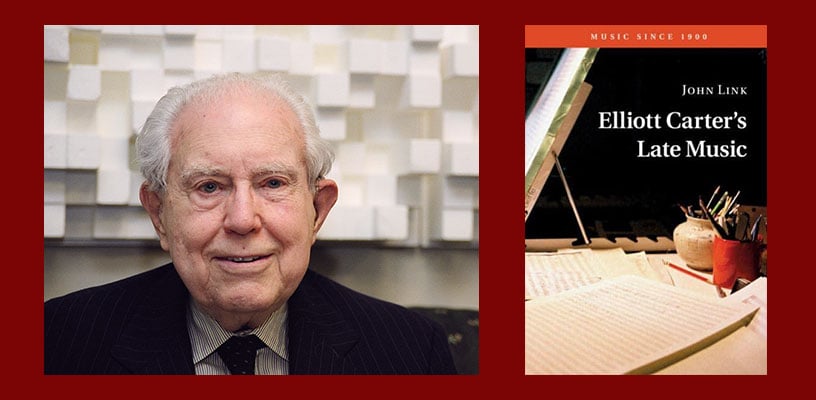

New Book Surveys Elliott Carter’s Late Music

The first comprehensive study of the late music of one of the most influential composers of the last half century, Elliott Carter’s Late Music by John Link places the composer’s music from 1995 to 2012 in the broader context of post-war contemporary concert music.

“Elliot Carter’s Late Music makes for absorbing, frequently demanding but always rewarding reading.” —Gramophone

Elliott Carter’s prolific career spanned over 75 years, with more than 150 pieces, ranging from chamber music to orchestra to opera, often marked with a sense of wit and humor. His astonishing late-career creative burst resulted in a number of solo and chamber works, including What Are Years (2009), Nine by Five (2009), and Two Thoughts About the Piano (2005-2006), as well as major contributions such as his opera What Next? (1997-1998), Three Illusions for Orchestra (2004), and a piano concerto, Interventions (2007), which premiered on Carter's 100th birthday concert at Carnegie Hall. He composed up until his passing at the age of 103 in 2012. (November 5, 2022 marks the 10-year anniversary of his passing.)

A new book, Elliott Carter’s Late Music, by composer and scholar John Link was published earlier this spring by Cambridge University Press. Link’s previous publications have included Elliott Carter: A Guide to Research, and he was co-editor with Marguerite Boland of Elliott Carter Studies, and with Nicholas Hopkins of Carter’s Harmony Book. Link’s latest Carter book addresses the composer’s reception history, his aesthetics, and his harmonic and rhythmic practice, and includes detailed essays on all of Carter’s major works after 1995, from his Fifth String Quartet through to his final work Epigrams.

We spoke with John Link about the new book, and about Carter’s late works in the larger context of the composer’s output.

Can you explain how you’ve approached writing about Carter’s late works, and how the book is organized?

One of the things I decided early on was that I wanted the book to be a collection of short to medium-length essays; one on each one of his pieces, rather than a kind of grand aesthetic summary of what the “late Carter style” is. I wanted to define his late work in the context of the individual compositions rather than the other way around.

The book is organized in three parts. Part I is context—I talk about Carter’s later music in the context of his earlier music and in the context of the tumultuous history of the 20th century and modernism. I have a chapter on Carter’s career and reception history, a chapter on his aesthetics, and two more technical chapters—one on harmony, and one on rhythm and form. Part II is about his text settings, including the opera What Next?, and the song cycles. Part III is on the instrumental music: orchestral music, concertos, music for large and small chamber ensemble, and then all the myriad short instrumental pieces that he wrote.

Carter was especially prolific in his later life. Are there any overarching themes or characteristics to his later works?

Certain preoccupations are consistent in Carter’s later music. One of them is writing for the voice and setting texts by the founding generation of modernist poets that were most active when Carter was a young person. So in the 1970s and early ’80s he set music by his contemporaries, Ashbery, Lowell, and Bishop; then later he returned to the earlier generation of modernist poets—T.S. Eliot, e.e. cummings, William Carlos Williams, and Wallace Stevens. So that was one important thread of preoccupation, and he wrote lots and lots of vocal music in his later years—at least one major piece every year. I put the vocal music in the second part of the book, ahead of the instrumental music even, because I think that was such an important aspect of his work.

Another important theme in Carter’s late music is that he went from writing pieces that were about social interaction—that is, instruments and groups of instruments interacting with each other like characters on a stage—to music in the early 1980s, like his Night Fantasies for solo piano, that were more about the internal life of a single persona. Then in the late music he began to realize that these two perspectives could be represented at the same time: In the Fifth Quartet, you have the interaction of four individuals, but at the same time you have the mind of the composer reviewing his previous work in the string quartet genre and writing about it. So what I call “lyric perspective” (the internal world of the mind as it works) can be represented in the same way that you can represent social interaction. Carter did this in several of his later pieces, where both of those ideas are represented at once, and that I find absolutely fascinating.

How does he approach character treatment in a dramatic work, like his opera What Next?

What Next? is a wonderful story, based on a scene from Jaques Tati’s film Trafic. After a huge multi-car accident, all of the occupants of the cars gradually emerge. And the comedy of the scene is that Tati treats them as though they are just waking up in the morning—they stretch their arms, one starts doing calisthenics, another brushes his teeth, and so on. But at first they aren’t very aware of each other.

This behavior is quite similar to the behavior of the characters in Carter’s instrumental music. The way he defines those instrumental characters is by giving each one unique harmonic and rhythmic materials. So that means that their interactions are somewhat limited, because they don’t share the same vocabulary, they can’t speak each other’s language in a way. And that makes them more like commedia dell'arte characters: archetypes rather than complex, changeable human beings or representations of human beings. The characters in What Next? are somewhat like the characters in Carter’s instrumental music. They exist somewhere between commedia dell'arte characters, which are archetypes, and real flesh and blood human beings. So he very much plays with the idea of what would happen if he and his librettist Paul Griffiths took these abstracted instrumental characters from his earlier music, and put them on stage as actual opera characters—how would they interact with each other? How could they communicate? What are their relationships? And so on. And I think that’s very much the subject of What Next?

What Next? is a critically important piece in Carter’s oeuvre and unfortunately one that has been somewhat neglected. The libretto has come in for a great deal of criticism in some quarters, unjustly I think, because it’s quite a brilliant libretto, and exactly what Carter was looking for. So I made this the centerpiece of the vocal music section of the book.

Can you tell us about how comedy figures into Carter’s works?

Carter was always very interested in comedy. He frequently talked about being influenced by Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and musical comedians like Harpo Marx and Chico Marx. All of this influenced him a great deal, and his music is filled with lots of comical interactions that sometimes people don’t recognize, because modernist music is “supposed” to be serious. They miss the comedy that Carter wrote into a lot of his music.

In almost every piece there’s some kind of comical element. For example, in Interventions, the piano and the orchestra are opposed to each other. One of the characteristics of the piano is to be very bold and flashy, and it often comes in with a bang. The orchestra, on the other hand, is rather hesitant and timid, but at one point there’s a complete reversal of those characteristics, when the piano is playing very softly and trailing off, and the orchestra suddenly comes in very loudly. Moments like that are sometimes disguised, but are very much intended to be comical inversions of what you expect.

His final piece Epigrams is another wonderful example of his comical sensibilities. It’s filled with all kinds of wonderful passages when the instruments are interrupted; there are all kinds of comic inversions and wonderful moments that are very moving, but it also has a streak of whimsicality to it, which I think is very characteristic of both Carter and of his music.

Any final thoughts for readers?

I wrote this book for readers who are interested in listening to Carter’s music, and who want to know a little bit more about it. This is not a treatise or a kind of theoretical tome; it’s more meant for listeners and for music lovers. The best way to approach Carter’s music is simply to listen to it, and let it tell you its own story. And if my book can help make that story easier to follow, then it will have served its purpose.

Elliott Carter’s Late Music

By John Link

Cambridge University Press

ISBN: 9780521769761

Published April 2022

Contents

Part I. Context:

Ch 1. Carter's career and reception history

Ch 2. The elements of an aesthetic

Ch 3. Harmony

Ch 4. Rhythm and form

Part II. A Literary Imagination (Text Settings):

Ch 5. Sense and sensibility – opera

Ch 6. A kind of light – song cycles and other text settings

Part III. Instrumental Music:

Ch 7. Illusions – music for orchestra

Ch 8. Social aspirations – music for instrumental soloist and ensemble

Ch 9. A free society – music for large chamber ensemble

Ch 10. Social relations – music for small chamber ensemble

Ch 11. Reflections – short instrumental pieces.