Brett Dean on The Last Days of Socrates

Brett Dean introduces his new work for bass-baritone, choir and orchestra, to be premiered in Berlin in April conducted by Simon Rattle.

What first appealed to you about The Last Days of Socrates as a subject?

The original suggestion came from my wife, Heather, while I was researching ideas for a possible future opera project. She is a visual artist and was painting a cycle of pictures dealing with the Socrates story, specifically the impact that his death must have had on the young Plato and other Socratic followers. Eventually, I came to the conclusion that the story was better suited to a concert setting with soloist, chorus and orchestra. When writing for chorus, I've always found it helpful to imagine what might motivate a large group of voices to unify in sound and song. In the same way that a solo instrumental concerto has, for me, great inherent drama in its pitting of one against many, so too the image of this extraordinary individual being tried (what's more, on trumped-up charges) in front of a jury of some 500 people seemed to carry with it great musical and dramatic potential.

How did you and poet Graeme William Ellis select the texts from Plato’s dialogues?

Though the work’s triple co-commission includes two orchestras (the Melbourne Symphony and the Los Angeles Philharmonic), the initial commission came from Simon Halsey and the Berlin Radio Choir with the explicit wish for a major choral-orchestral work in which the choir takes a central role. This drew us quite naturally to pivotal ‘peopled’ scenes of the Platonic dialogues, specifically the Apology in which Socrates argues his case before the court, and Phaedo, in which he awaits his death in the company of his followers. The Melbourne-based poet, Graeme William Ellis, has adapted aspects of these particular writings as well as other strands of philosophical thought attributed to Socrates and prefaced them with a ‘scene-setting’ hymn to the Goddess Athena.

With Socrates being such a wide-ranging thinker on politics, religion and morality, what aspects did you particularly focus on?

Taking these two scenes as our starting point, we felt it was important to acknowledge Socrates' ongoing significance for us today. To this day, he demonstrates more than any other philosopher that any life, indeed every life is open to aspects of philosophy. By making a stand for causes of liberty and justice, an individual can be no less subject to persecution and repression nowadays as they have been in the past. Thus I was interested in drawing links between the principles that Socrates stood for, (above all, his search for self-knowledge by asking questions and humbly acknowledging what one doesn't know) and the motivations behind ‘Socratic’ protagonists in our own time. One such example is to be found in the writings and actions of the Chinese dissident artist, Ai Weiwei which reflect a Socratic understanding of ethics and the necessity to make individual moral choices. ("Liberty is the right to question everything".) Furthermore, Graeme William Ellis takes the idea - attributed since antiquity to Socrates - of the beauty and significance of a swan's final song in the moment of death, as a metaphor for the visionary Socratic concept of death being the ultimate fulfillment of an ethical and well-lived life. ("How we live here decides on that other life.").

The work offers two scenas for bass-baritone soloist. How operatic were your intentions, knowing you were writing for John Tomlinson?

As I mentioned, this work came about through the search for a planned opera project. While Graeme's text is a vessel for philosophical ideas, something of its dramatic stage potential can still be found in the argumentative, stand-off nature of the trial in the second movement. This sense of confrontation occurs not only between Socrates and his accusers (semi-chorus of tenors and basses), but also between them and his supporters (sopranos and altos). To this end, the magnificent singer-actor John Tomlinson (whom I've admired since my earliest days as a violist in the Berlin Philharmonic where he's been a regular guest artist for over 20 years, and whose realisations of roles such as Wotan, Baron Ochs and the Minotaur are legendary) seemed ideally suited to the portrayal of our version of Socrates, by turns curmudgeonly argumentative and lyrically reflective.

How do you musically balance the work’s classical setting with a modern approach?

I've always been fascinated by Stravinsky's well-documented choice, in Oedipus Rex, to use a Latin text to deliberately create a distance between the work and its audience, to bring about a conscious abstraction and not to simply "tell the story". This thought occupied me in the early stages of conceiving Socrates and certainly Graeme's opening Athenian chorus, although written in English like the remainder of the work, carries with it something of a classical distancing rather than launching straight into the drama of the Apology.

However, we also revisit and reinvent the classics largely to uncover what contemporary relevance they may offer us. The Socrates story transcends eras and raises questions relevant for all humanity in all epochs. It’s a story which is hovering whenever we witness the attempts of free-thinking opposition to state control, for example. Our approach is built on the inherent energetic and dramatic discourse of this very real human drama which, although having taken place well over 2000 years ago, still resonates with us. One could tell this universal story in a myriad of contemporary or stylized ways; in this instance it’s told using a modern choral/orchestral setting which I feel contains both message and mystery.

How have you moved from orchestral and instrumental scores to writing for voices and chorus in recent years?

My first major work for solo voice was the song cycle Winter Songs for tenor and wind quintet written in 2000 to texts of e.e.cummings. I've written a lot for voice in the decade since then, with three further song cycles, several choral works and an opera. And it's no coincidence; both of my daughters are accomplished singers with significant choral experience gained through their time with the extraordinary Gondwana Voices children's choir in Australia and going on to further vocal studies at a tertiary level. They both provide me with ready feedback and tryouts of my vocal lines, and have given me a keen insight into the process of music-making as experienced by singers.

As in your recent Fire Music you employ unusual groupings and spatial elements.

Yes. I've been experimenting with spatial elements in my music for quite some time, often in site-specific circumstances outside of the concert hall. Trying to capture something of this in the concert hall is a special challenge and can suffer from the simple fact that somebody sitting coincidentally right near one of the satellite groups may hear nothing but the third trumpet part all night long. So the spatial thing needs careful consideration. Nevertheless the sonic, dramatic and poetic potential of it remains irresistible.

In The Last Days of Socrates a distant group of violins in the first movement is echoed by an offstage group of female voices in the final movement, used ostensibly as instruments. The orchestration uses the distinctive, street-wise colours of the accordion and the electric guitar in addition to extensive use of terracotta and metal percussion sounds, inspired by the legend that the verdict of guilt or innocence in Athenian courts was reached by ordering the jury members to cast one of two different types of metal disc or coin into large terracotta vats.

What's more, being in essence a work about the philosophical and moral potential of the individual, the score is inhabited by a large cast of individual protagonists; not only the bass-baritone role of Socrates himself and the solo and multi-layered uses of the choral forces, but also within the orchestral fabric, including significant moments for the six horns, for three solo double basses and a long reflective cello solo at the opening of the final movement, written in memory of Berlin Philharmonic cellist Jan Diesselhorst, one of the most philosophically minded musicians I ever had the pleasure to meet.

Interviewed by David Allenby, 2013

<dir=ltr align=left>

Brett Dean

The Last Days of Socrates (2012) 40’

for bass-baritone, SATB chorus and orchestra

Text by Graeme William Ellis (E)

Commissioned by RundfunkChor Berlin, Los Angeles Philharmonic and Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

25 April 2013

(world premiere)

Philharmonie, Berlin

John Tomlinson/Rundfunkchor Berlin/Berliner Philharmoniker/Simon Rattle

26 July 2013

(Australian premiere)

Robert Blackwood Hall, Monash, Melbourne

Peter Coleman-Wright/Melbourne Symphony Orchestra and Chorus/Simone Young

10/11/12/13 October 2013

(US premiere)

Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles

Los Angeles Master Chorale/Los Angeles Philharmonic/Gustavo Dudamel

> Further information on Work: The Last Days of Socrates

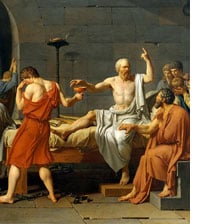

Painting: The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Louis David