John Adams in interview about his new oratorio El Niño

John Adams discusses his new Nativity oratorio, receiving its premiere in Paris on 15 December, followed by performances in San Francisco and Berlin

How did the idea of a piece built around the Nativity first come about?

The piece is my way of trying to understand what is meant by a miracle. When I recently reread some of the New Testament gospels I was struck as never before by the fact that most of the narratives are little more than long sequences of miracles. I don't understand why the story of Jesus must be told in this manner, but I accept as a matter of faith that it must be so. The Nativity is the first of these miracles, and El Niño is a meditation on these events. In fact, my original working title was How Could This Happen? This phrase, taken from the Antiphon for Christmas Eve, also must surely have been uttered by me at the births of my own son and daughter.

Entering into this myth, making art about it and finding your own voice to express it can't help but put you in a very humble position. You realize that you're just another artisan, laying a single stone in an edifice that is already centuries old and infused with the effort and genius of many who have gone there before and done it better than you. Perhaps that is why one might detect a certain medieval quality to some of what I've written in this piece. That quality is not there as an exoticism but rather as an artifact, a "tonality" that frames the emotion of the work.

El Niño shows a continuing interest in Hispanic culture, following on from works such as El Dorado, the character of Consuelo in Ceiling/Sky, your tango arrangements...Why is this so important to you?

The idea of incorporating Hispanic texts into the libretto came from Peter Sellars, who I'd asked to help me construct a libretto. We both call California home, and the intensity and genuineness of Latin American art and culture is one of the great gifts one receives by living here. Of the five Hispanic poets whose texts I've set, three are women. This opened up possibilities of adding another dimension to the story-telling. So much of the 'official' Nativity narrative has traditionally been told by the Church, and presumably by men. But seldom in the orthodox stories is there any more than a passing awareness of the misery and pain of labour, of the uncertainty and doubt of pregnancy, or of that mixture of supreme happiness and inexplicable emptiness that follows the moment of birth. All of those extreme emotional dramas surrounding the birth of a child are touched upon by these Hispanic women.

The two major voices in El Niño are both Mexican women. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, was a 17th century nun whose ecstatically-revealed poetry puts her in a class with Hildegard von Bingen and Emily Dickinson. Sor Juana is exceptionally famous in Latin countries, thereby making the challenge of setting her poetry something one does only with the greatest respect and care. The other great poet, four of whose poems provide the deepest psychological intuitions in the piece, is Rosario Castellanos. She was a 20th century novelist from Chiapas, the mountainous southern state of Mexico where the most "indigenous" of its people live. She is as equally great a poet as Sor Juana, but being more modern, her imagery is more familiar to us, and her descriptions of pregnancy, labour, sexual union and the physicality of birth give El Niño a reality that it otherwise would lack.

You've also included religious texts that stand outside the Biblical canon.

Yes, the Hispanic texts are interwoven with other Nativity texts, some familiar, such as Luke and Matthew, and others not so familiar, such as the little-known Gnostic Infancy Gospels. These "pseudo-gospels" (as the Church so calls them) were written at roughly the same time as the New Testament Gospels. Some are like children's stories or fairy-tales, while others are every bit as serious and probing as the official gospels. In the Gospel of James, for instance, there is a psychological shading, a subtlety about human relations, even humour, that is not so apparent in either Luke or Matthew.

The title of El Niño, 'the little boy', also conjures up allusions of hurricane-force winds.

My choice of title is admittedly provocative, given how it has become recently linked in people's minds with stormy and violent weather. In Guatemala it must surely come with a bitter association of a calamitous natural energy, which caused terrible misery and grief for millions of poor people only a few years ago. But that association is right. As Sor Juana so often says, a miracle is not without its alarming force. Herod knows this. We all know it when a child comes into the world. It comes with both the potential to do evil and the power to bring love.

The work appears closest in form to a traditional concert oratorio, yet theatrical stagings are also planned. How did the twin presentation possibilities evolve?

I want the work to be flexible and not be tied to any one way of presenting it. In Paris in December and in San Francisco the following month, it will be in the form of a staged production by Peter Sellars that includes a film he made for it and dancers alongside the singers. But I also envision the work as a straightforward concert work in the manner of Messiah. Equally, I don't see the piece as "site-specific" to Christmas. It should be and it is a matter for us at any time of the year.

Interviewed by David Allenby

Future performances

with soloists Dawn Upshaw, Lorraine Hunt-Lieberson and Willard White

conducted by Kent Nagano

| 15/17(m)/19/20/22/23 December | Paris, Théâtre du Châtelet |

| 11/12/13 January | San Francisco, Symphony Hall |

| 15/16 April | Berlin, Philharmonie |

> Further information on Work: El Niño

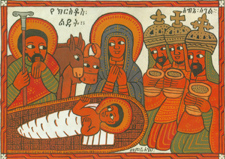

Illustration: a modern Ethiopian Nativity painting (Photo: © Meryl Doney)