Cherubini's Médée: tragédie lyrique version reclaimed

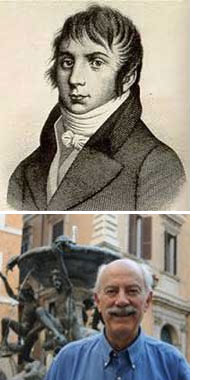

An interview with Alan Curtis explains how his new recitatives are helping restore Cherubini's classic opera Médée to its original tragédie lyrique form. The new version is staged for the first time at the Theater Ulm, opening on 5 February.

You are well known in the opera world as a baroque opera specialist and interpreter with an enormous joy of discovery. Your name is definitely not associated with the music of Luigi Cherubini. What happened?

What happened was, I would say, a mistake – not mine but history’s! Because Médée became popular only in the 19th-century, and again in the 20th thanks to the passionate portrayal of the title role by Maria Callas in a 19th-century Italian version, Medea, many people consider the opera part of the 19th-century repertoire – definitely NOT my field. However, it is in fact a late 18th-century opera, from the same period as for instance Cimarosa’s Gl’Orazii e Curiazii, an opera that I often conducted some years ago in Rome, Lisbon, and elsewhere (it was the debut of Anna Caterina Antonacci, who later sang and recorded for DVD Cherubini’s Medea!). I approach Médée from its own century, the 18th. But in any case, I would consider it a masterpiece no matter when it was written!

What does Cherubini's music mean to you? What causes your personal fascination for this composer?

I find his music both passionate and elegant, and occasionally quite humorous. I am fascinated, especially in the early works, by the energy and force of someone struggling to free himself from the bonds of tradition, which he nonetheless respects. I am also interested in how foreigners like Gluck, Piccini, Sacchini and Cherubini adapt their music for French tastes.

Why don't the operas of Cherubini, in your opinion, get the attention in the international repertoire they deserve?

It is difficult to understand, much less to make sense of, changes in popularity. Tastes in opera swing with the pendulum of fashion. Neo-classical composers like Gluck, Traetta, Jommelli, Sacchini and later Méhul and Cherubini are all underrated today, in my opinion. I personally find it impossible to overrate Handel, whose music I adore, but I must concede that he is nowadays having his day (after waiting – so far as his operas are concerned – for over two hundred years!) and with regret anticipate that he may be heard less after the next major change of fashion. I do think that Cherubini will again come to be more highly esteemed by the public when it is finally given a chance to hear his music.

Cherubini himself composed his Médée as an opéra-comique with self-contained musical numbers and spoken dialogue. In the 20th century, an Italian version from 1909 with recitatives by Franz Lachner became popular. How do you view the necessity (or the opportunity) to create new recitatives for the 21st century, when these recitatives are of course not written by the composer Cherubini? What caused you to write new music for the originally spoken dialogue?

Why Cherubini’s Médée ended up as an opéra comique is a subject not yet carefully studied. The librettist, Hoffman, an established writer who had already worked on several occasions for the Royal Opera in Paris, wrote the libretto as a tragédie lyrique, which means that the text we know as spoken dialogue, was actually intended to be set to music (as accompanied recitative). The composer first commissioned to write music for this libretto was not Cherubini, but the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne. The project failed, the contracts were annulled, and the project was later taken on by the Théâtre Feydeau where only opéra comique – opera with spoken dialogue – was allowed to be played. Cherubini himself did not later rework the piece according to its original conception as a tragédie lyrique, as Hoffman conceived it, probably because it was not a great success at the premiere and he was busy afterwards writing other operas. Médée was in many ways an "Artwork of the Future". In any event, today more than in Cherubini’s time, opera singers are NOT noted for their ability to interpret and project spoken texts. Moreover even (perhaps especially!) French-speaking audiences seldom want to have the musical part of an opera interrupted by speech. Of course Lachner’s version has (often without thinking) been generally accepted over the years, but with the original French text translated into German, and then into Italian, quite a bit has been lost. We should also remember that Lachner’s idol and model was Wagner. He lived in an age when interest in 'historical' music was just beginning and there was no sense of wanting to restore the actual sound an 'antique' composer might have had in mind. I propose my recitatives primarily not because they are better (though I think they are), but because they are based on examples from Cherubini’s own output.

What is the significant difference between your recitatives and Lachner's intentions?

I presume that Lachner had respect for Cherubini as a composer, but it seems obvious that his intention was not to respect Cherubini’s style, but simply to compose expressive German music as best he could in a then modern Wagnerian style. I have (like Cherubini) started with the original French text, tried to express it in a manner similar to Cherubini’s and only then given vent to my own compositional preferences.

Setting the spoken dialogues into music has consequences for the structural conception of an opera. What kind of effect do these (now sung) recitatives have on the specific style and especially on the musical and dramaturgical flow?

I can hardly pretend that I have not changed the 'dramatic flow', but my aim was to improve it. I do hope that I have respected the essentials of the original dramaturgy, and even of stage necessities (for instance where the chorus must exit I have inserted a passage based on a similar place in another opera by Cherubini). I also think the changes, especially the shortening of the dialogues, help a modern audience to focus on what is most interesting for us today – Cherubini’s music – without doing violence to the original text.

What is typical Cherubini style in your recitatives? Or is it 100% Curtis?

As already mentioned, I have sometimes 'borrowed' from Cherubini himself, but always with some changes – not to disguise the borrowing (for who today would recognize quotes from other early operas by Cherubini?!) but to adapt the music, as Cherubini himself might have, to the different text and similar but not identical context. A result of my following Cherubini, unlike Lachner, is that my recitatives are generally simpler, more direct, and shorter, something which helps concentrate attention where it belongs – on Cherubini’s music, not mine.

Is it really possible to add to or 'complete' a 200-year-old opera in the manner or style the original composer would have employed? Or is it already a subjective interpretation of a work?

Without pretending to have 'completed' the opera as Cherubini might have, I nevertheless feel happy that I may have helped him to finally be heard and respected as the composer of a fully-fledged tragédie lyrique, in which the lofty ideas expressed in his extant music are allowed to be heard with only minimal interruptions. I cannot judge whether my 'interpretation' is more or less subjective than Lachner’s, but I know that my interruptions are shorter, less disturbing stylistically, and closer to Cherubini than to Wagner.

Médée (new production)

New version with recitatives by Alan Curtis

Theater Ulm

5 February 2015 (opening night)

7/10/14/22/27 February

6/12/29 March; 17 April; 3/13/27 May

Conductor: Daniel Montané

Director: Igor Folwill

> Theater Ulm website

Alan Curtis and the Complesso Barocco Edition

Alan Curtis has been a pioneer in the return to original instruments and Baroque performance practices, especially in the field of early opera. In over 35 years of performing concerts and recordings together, he and his group of singers and instrumentalists, Il Complesso Barocco, have not only brought to light many important works that had been forgotten or undervalued, but have also revealed new aspects of even the best-known masterpieces of the era from Monteverdi to Mozart.

The Complesso Barocco Edition, published by Boosey & Hawkes, is a selection of the most important of these works, with a particular focus on operas and dramatic oratorios. Many of the works in this series will be published not only in full score, but also in a set-out piano-vocal score as a study help for singers and stage directors. The series includes Drama Queens – 13 selected arias recorded and toured by Joyce DiDonato, Vivaldi's Catone in Utica and Gluck's Demofonte.