Symphony No.5: 'Le grand Inconnu'

(The Great Unknown) (2018)St John of the Cross (E), Veni Creator (E) Biblical (E, L), H,L,G words

2.2.2.2(II=dbn)-4.2.3.1-timp.perc(2):crot/lg metal bar or pipe/wind machine/sizzle.cyml/tam-t;glsp/t.bells/tgl/BD/thundersheet-harp-pft-str

Abbreviations (PDF)

Boosey & Hawkes

The symphonic tradition, and Beethoven’s monumental impact on it, is an imposing legacy which looms like a giant ghost over the shoulder of any living composer foolhardy enough to consider adding to it. Perhaps not fully knowing what writing a symphony “means” any more, some of us are drawn towards it like moths flapping around a candle flame.

My fifth symphony turned out to be a choral symphony, if very different to Beethoven’s. It came on the back of my Stabat Mater and was commissioned from the same source and involved the same performers. The philanthropist John Studzinski has taken a great interest in The Sixteen and has a special concern for sacred music. It was he who, along with Harry Christophers, suggested I write my own Stabat Mater. After that he began talking to me about how the concept of the Holy Spirit has been handled in music.

There are, of course, many great motets from the past which set texts devoted to the Third Person of the Trinity, and in the 20th century the one piece which sticks out is the setting of the Veni Creator Spiritus in the first movement of Mahler’s Eighth Symphony. But it still feels like relatively unexplored territory, so perhaps now is the time to explore this mysterious avenue, where concepts of creativity and spirituality overlap? There is a real burgeoning interest in spirituality in our contemporary post-religious and now post-secular society, especially in relation to the arts. Music is described as the most spiritual of the arts, even by non-religious music lovers, and there is today a genuinely universal understanding that music can reach deep into the human soul.

It makes sense surely that a Catholic artist like myself might want to explore this in music, perhaps even beyond the usual hymnody and paeans of praise associated with liturgy. My fifth symphony is not a liturgical work. It is an attempt to explore the mystery discussed above in music for two choirs and orchestra. It began when John Studzinski gave me a copy of ‘The Holy Spirit, Fire of Divine Love’ by the Belgian Carmelite Wilfred Stinissen. It was a good point of entry, theologically, but it also called to my attention some visionary poetry by St John of the Cross. This line from the book in particular drew me in; “Even his name reveals that the Holy Spirit is mysterious. The Hebrew word ‘ruah’, the Greek word ‘pneuma’ and the Latin ‘spiritus’ mean both ‘wind’ and ‘breath’”, and these words provided the very first sounds heard in my symphony.

The work, to begin with, is less a traditional setting of text and more an exploration of elemental and primal sounds and words associated with the Spirit. The first movement is called ‘Ruah’, the second ‘Zao’ (ancient Greek for living water) and the third is ‘Igne vel Igne’ (Latin for fire or fire). So, each has associations with the physical elements connected to the Holy Spirit (wind, water, fire). These became vivid sources of visual and sonic inspiration. The fifth symphony has a subtitle – ‘Le grand Inconnu’ a French term used to describe the mystery of the Holy Spirit which I cannot find replicated in the English spiritual tradition.

Sound associations and impressions guided the choice of texts in each of the three movements and often dictated the overall structure; which bits of St John of the Cross to use, which corresponding moment in Scripture might amplify or reflect the general direction, which sounds to use in the orchestra as well as extended vocal sounds in the choir which were not necessarily sung. As well as breathing noises, there are whisperings and murmurings, devised to paint the required element from moment to moment.

The two choirs in the fifth symphony are a chamber choir and a large chorus. At the end of the second movement I divide these two ensembles into 20 parts, offering a parallel to the multi-voice writing of Vidi Aquam, a 40-part companion piece to Tallis’s Spem in Alium that I was composing at the same time as the symphony, and providing a means to continue communing with the English Renaissance master.

James MacMillan, 2019

Reproduction Rights

This programme note can be reproduced free of charge in concert programmes with a credit to the composer.

Choral level of difficulty: Level 5 (5 greatest)

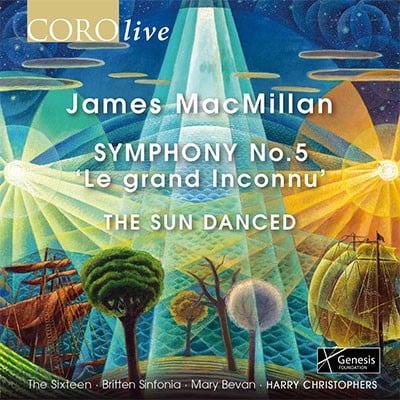

This is one of MacMillan’s most recent major works premiered in 2019 by the Sixteen with the Britten Sinfonia conducted by Harry Christophers who has become one of MacMillan’s greatest interpreters. It was commissioned by that remarkable philanthropist John Studzinski through his Genesis Foundation which has supported this partnership so regularly and wholeheartedly.

MacMillan writes of the symphonic tradition and Beethoven’s ‘monumental impact on it’ being an ‘imposing legacy which looms like a giant ghost over the shoulder of any living composer foolhardy enough to consider adding to it’. This may be what it feels like in the consideration of the task ahead for him, but it will surely be MacMillan amongst a few other ‘greats’ to whom future generations will look back as their benchmark and be ‘drawn to it like moths flapping around a candle flame’.

Again, it is the depth of MacMillan’s imagination which we marvel at. There is always a new approach in the way a project is considered. In this case John Studzinski gave MacMillan Wilfred Stinissen’s book The Holy Spirit, Fire of Divine Love which contained this line “Even his name reveals that the Holy Spirit is mysterious. The Hebrew word ‘ruah’, the Greek word ‘pneuma’ and the Latin ‘spiritus’ mean both ‘wind’ and ‘breath’“. And it is these words provided much of the impetus and inspiration for the approach to this work. The first movement is called Ruah, the second Zao and the third Igne vel Igne (Breath or Spirit, Living Water, and Wind, Water, Fire).

The symphony begins with actual breathing, barely heard at first but building as instruments also add their breathing sounds and strings gently tap their fingerboards and as this develops the sound is extraordinarily like gently moving water. It is a curiously moving effect. And as MacMillan says, the symphony is not a traditional setting of words – though there are words set – but he is more interested in the exploration of sound associated in his mind with the Spirit. MacMillan is adamant that, for all its religious associations, it is not a religious work, but it is spiritual, connecting with the post-modern interest – even preoccupation - with spirituality which may or may not meet in liturgical space. So it is the connection with our hunger for meaning, and a reassessment of our place in the world which this work addresses.

There are so many remarkable elements to it that it is almost invidious to pick some out, but the twenty-part chorus at the end of the second movement reminds us that he was also working on Vidi Aquam, his 40-part motet paying homage to Tallis’s masterpiece Spem in Alium. He is a master of choral texture and sonority as the start of the final movement also reminds us. The relentless building of the first movement from its almost inaudible opening to its bubbling energy later on is typical of this composer who can work on such large-scale canvasses and in such long paragraphs. That in itself is a mark of his particular genius. Who, also would think of ending the second movement with crash into the buffers at full tilt with no warning. It takes the breath away. Bach looms large in the gentle piano writing accompanied by strings in the third movement – Mahler, too… but these are like little glances back (as with Tallis) as if to seek the approbation of these masters before he moves back fairly and squarely into his own hard-won territory and reminds us that he is the leader of the pack in our time.

This is a major undertaking for whoever programmes it but the journey is such a powerful experience that with the right forces capable of realizing the demands, and the right person in charge, this becomes the journey of a lifetime. It is a musical Camino.

Repertoire Note by Paul Spicer

“…a meditation on the nature of the Holy Spirit – the ‘great unknown’ of Catholic theology. It is cast in three sections representing breath, water and fire. The work opens on whispered breaths, the sound coalescing into chanting of the Hebrew, Greek and Latin words for breath amid mysterious rustlings in the orchestra. Later this explodes into a series of dramatic, ecstatic climaxes… MacMillan’s writing for voices is utterly assured.”

The Guardian

“…there was no mistaking the outflow of ecstatic passion that drove the compositional process. It opens in surreal territory, amorphous intakes of breath that turn to specific words, eventual pitched sounds punctured by microtones and harmonics paving the way for a turbulent three-movement adrenalin rush of all that MacMillan is known for.”

The Scotsman

“At the end of the second part a memorable passage has the choir divided into 20 parts, harking back to the Tudor era. At the end the living fire flickers and fades… The feeling lingers that MacMillan is searching his subconscious in a way he has not before… This numinous symphony will surely reward other audiences prepared to listen with the patience and concentration it deserves.”

Financial Times

The Sixteen/Genesis Sixteen/

Britten Sinfonia/Harry Christophers

Coro COR16179