fl(=picc).cl(=bcl).bsn(=dbn)-tpt-perc(1):tabor/marimba/wdbl/

4rototoms/3susp.cym(high/med/low)/SD-strings(1.0.1.1.1)

Abbreviations (PDF)

Boosey & Hawkes

Robert Burns craved the gift "to see ourselves as others see us" and it can indeed be an illuminating, if even devastating experience to see or hear how one is perceived by others. This must especially be the case when one’s characteristics are captured on canvas, in print, or in music.

In composing these ‘sound paintings’ of prominent figures whose portraits hang in the National Portrait Gallery I was attempting an objective character analysis of each one, from my own particular perspective. In order to maintain this distance throughout, I use an old Scottish dance tune which is transformed from one piece to the next to capture the character and the historical context of each portrait.

1. Henry VIII (1491-1547)

Over a driving riff the Scottish tune is blared out in parallel harmonic layering in a raw parody of a Tudor dance. The music is butch, macho and has an almost bullying manner. Gradually other elements intrude to convey the brutality and egotistical madness of this misogynistic tyrant. For example, Henry’s famous composition Greensleeves which, over the next few centuries, was performed at public executions in England and in Europe - an apt use of a tune whose composer callously sent wives, friends and countless subjects to their deaths.

2. John Wilmot (1647-1680)

In this portrait the outrageous court poet bestows his laurels on a monkey who is busily destroying the poet’s verses. The opening slow, sustained, dignified string music represents ‘The Muse’; the darting, scurrying material on wind and percussion represents the cheek of the monkey. Gradually the two musics influence each other, and after passing through the rhythms of the French overture (popular in the court at this time), the Poet becomes Monkey and Monkey becomes Poet.

3. John Churchill (1650-1722)

The central figure here is the conquering martial hero whose physical strength and power are conveyed on trumpet and percussion. Subservient to him is Hercules portrayed by clarinet and bassoon. Swirling floating figures above are represented by big repetitive material on flute, violin and viola, and the dishevelled figure of Discord being trampled into the ground is given appropriate music on cello and double bass.

4. George Byron (1788-1824) and William Wordsworth (1770-1850)

The dashing, romantic figure of Byron (an Anglophile Scot) is represented by energetic material which at time gives some inkling of 19th century romantic musical heroes - Wagner’s Lohengrin and Strauss’s Don Juan. Wordsworth is more brooding and reflective in character and if there is any allusion to 19th century music then it is to the poignant slow movement of Beethoven’s 7th Symphony.

5. T.S. Eliot (1888-1965)

I attempt to capture the split personality of this poet, seen in this cubist portrait by Patrick Heron. I took the two profiles to refer to his dual national characteristics - this American who was fascinated by England and especially by High Anglican ritual. Therefore his Englishness is captured by a quasi-liturgical music, and his American-ness is presented in a 1920s jazz style for which he was reputed to have a keen interest.

6. Dorothy Hodgkin (1910-1994)

As if to indicate the depth of this woman’s intellect I have the strings playing a solemn and serene series of chords over which I attempt to achieve a gradual synthesis of two separate processes. It is as if she is trying to find some scientific solution of which the two basic elements are: a) a melodic interaction between violin and clarinet and b) an imploding durational process on piccolo, trumpet and contrabassoon. The two processes, as if by chemical reaction, gradually merge to become one single element.

James MacMillan, August 1997

Reproduction Rights

This programme note can be reproduced free of charge in concert programmes with a credit to the composer

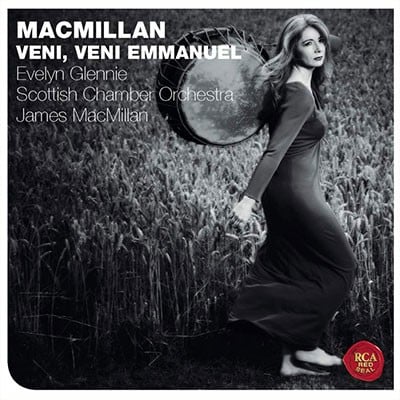

Scottish Chamber Orchestra / James MacMillan

(p) and (c) 1993 BMG Music

RCA G010001846447Z