Christmas Oratorio

(2019)Biblical (E), Liturgical (L), Traditional (Scottish Gaelic), Southwell (E), Donne (E), Milton (E)

2.2.2.2-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(2):xyl/tgl/cabasa/snare.dr/BD/tam-t/vib/wdbl/metal.pipe(or anvil)/2timbales/hi-hat/susp.cym-harp-cel-strings

Abbreviations (PDF)

Boosey & Hawkes

PART ONE

- Sinfonia 1; orchestra

- Chorus 1; chorus and orchestra

- Aria 1; soprano solo and orchestra

- Tableau 1; soli, chorus and orchestra

- Aria 2; baritone solo and orchestra

- Chorus 2; chorus and orchestra

- Sinfonia 2; orchestra

PART TWO

- Sinfonia 3; orchestra

- Chorus 3; chorus and orchestra

- Aria 3; baritone solo and orchestra

- Tableau 2; soli, chorus and orchestra

- Aria 4; soprano solo and orchestra

- Chorus 4; chorus and celesta

- Sinfonia 4; orchestra

My Christmas Oratorio was written in 2019 and is a setting of assorted poetry, liturgical texts and scripture taken from various sources, all relating to the birth of Jesus. It is structured in two Parts, each consisting of seven movements.

Therefore the music of each Part is topped and tailed by short orchestral movements (four in all), creating a palindromic structure. The Choruses are mostly Latin liturgical texts (although the last one is a Scottish lullaby), the Arias are settings of poems by Robert Southwell (2), John Donne and John Milton, and the two central Tableaux are biblical accounts from the Gospels of St Matthew in Part 1, and St John in Part 2.

The soloists, who have two arias each, are a soprano and a baritone, (and they sing in the two Tableaux along with the choir). The orchestra is of modest size, using double woodwind, brass and percussion, plus a harp and celesta.

There are various characteristic elements and moods throughout, from the ambiguous opening which mixes resonances of childhood innocence with more ominous premonitions, pointing to later events in the life of Jesus. There are also intermittent moments of joyfulness and the childhood excitement and abandon of Christmas at various points, especially in the choral Hodie Christus Natus Est and in some of the orchestral interludes.

Sometimes we hear the ‘dancing’ rhythms associated with some secular Christmas carols. There is also, at points, a sense of narrative when the chorus take the role of the Evangelist as he tells the Nativity story. The 16th and 17th century English poems provide opportunities for reflection in the four solo Arias, firmly based in the oratorio tradition.

There is also at points a sense of mystery in both orchestral and choral textures, such as in the setting of the O Magnum Mysterium text in Part 2. The oratorio ends reflectively in Sinfonia 4 with the orchestra alone, highlighting a small ensemble of string soloists amid the larger textures.

James MacMillan, 2020

Reproduction Rights

This programme note can be reproduced free of charge in concert programmes with a credit to the composer

Choral level of difficulty: Level 4-5 (5 greatest)

Written in 2019, this oratorio is one of MacMillan’s most recent large-scale scores lasting just under two hours in two separate parts. It was commissioned by orchestras in London, Melbourne and New York, together with the leading Amsterdam radio concert series. It was premiered in Amsterdam instead of London where the COVID pandemic prevented its performance. It is a fascinating work – and again we marvel at MacMillan’s ability to divorce himself completely from Bach’s iconic work of the same name whilst obviously wanting to write his own version of the same concept, as with his Passions. Nothing could be clearer in this fresh approach than the opening which is redolent of Christmas carols we all know and love, child-like innocence – all 6/8 and baubles. It is delicious. But then look at his setting of Robert Southwell’s Behold a silly tender babe so well-known from Britten’s A Ceremony of Carols and see this soprano solo aria and its pure MacMillan soundscape. In a work this size it is almost invidious to single out individual sections but one of the most gently MacMillan-esque is the Hodie salvator apparuit in Part 1 (figure 48) which has unaccompanied choir with a wonderfully attractive dancing violin solo. This is interrupted by an orchestral interlude before calming down to take the movement to its end. In Part 2 his extraordinary setting of Hodie virgo, cujus viscera demonstrates, again, his exceptional ability with counterpoint. This unaccompanied setting has us in mind of Palestrina and yet it is pure MacMillan. Another comes in the fourth chorus My love and tender one. There is something in these settings which seems to resonate with MacMillan’s own feelings as a father. The use of the celesta at the end of this sounds like the wind chimes which fascinate any baby looking up from its pram. The final movement is purely orchestral. We are again reminded of how eclectic MacMillan can be, and how he can tug at our heart strings with the most romantic-feeling music. How far contemporary music has come since the heady and, for many, unfriendly days of the late twentieth century. This is a fabulous conception.

The work is structured around an assortment of poetry, liturgical texts and scripture relating to Jesus’s birth. There are seven movements in each Part. MacMillan writes ‘the music of each Part is topped and tailed by short orchestral movements (four in all), creating a palindromic structure. The Choruses are mostly Latin liturgical texts (although the last one is a Scottish lullaby), the Arias are settings of poems by Robert Southwell (2), John Donne and John Milton, and the two central Tableaux are biblical accounts from the Gospel of St Matthew in Part I and St John in Part 2’.

MacMillan has married the joy of the birth of a child – and this child in particular – with a feeling for the tragic end to his all too short life. As in his St Luke Passion, the role of the Evangelist narrating the story is taken not by a soloist but by the chorus, and the arias setting the earlier English poetry are all, as MacMillan acknowledges, firmly in the oratorio tradition.

The orchestration is for normal-sized symphony orchestra with two percussion players in addition to the timpani. The choral parts in this work are not frightening (which doesn’t mean that there are not challenges along the way) and it is surely manageable by any organization with the necessary resources to mount such a large-scale work. This is a deeply affecting, moving and involving work which will stay with the performer and listener for a long time after experiencing it. The mix between the associations we all have with music for this season, the telling of the nativity story in all its mythological wonder, together with the hindsight (or perhaps premonition) of Jesus’s life as a triumph leading to tragedy is all here. It is a world of experience and what a great thing that it takes the whole evening so that it can’t be watered down by a popular work simply to achieve ‘bums on seats’! It would be my sincere hope that MacMillan, as one of the true greats of our day, would achieve that by himself.

Repertoire Note by Paul Spicer

"...one of MacMillan's finest ever pieces... a heady mix of wonder, trepidation and profound mystery..."

BBC Music Magazine

“Even by MacMillan’s standards this is stunning music: profusely, lushly lyrical and often grounded in traditional tonality, yet infused with dazzlingly original instrumental and vocal ideas”

The Times

“The Kaleidoscopic Christmas Oratorio is a masterpiece… MacMillan can paint fantastically with timbres”.

De Trouw

“…a rich and prodigious invention… Highly dramatic, colourful, by turns ecstatic and rapt, it throws all of MacMillan’s irons into the fire to forge a full-scale, 100-minute tableau on the theme of the nativity…”

Financial Times

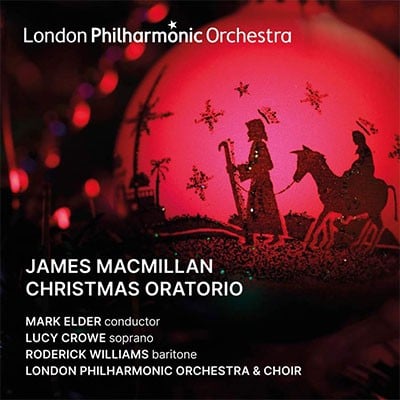

Lucy Crowe/Roderick Williams/

London Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir/

Mark Elder

LPO 0125