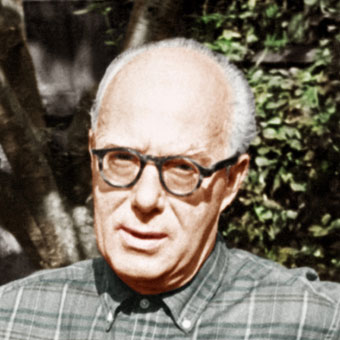

Roberto Gerhard

An introduction to Gerhard’s music

by Calum MacDonald

Roberto Gerhard ended his career in the very forefront of musical modernism, producing in his last 15 years a series of scores notable for their scintillating textural invention and their almost Varesian cragginess of expression. (Metamorphoses, a far-reaching revision of his Second Symphony that amounts to a separate work, was the very last of these.) Their undeniable power – and the aura that automatically adheres to a gifted pupil of Schoenberg – tend to dominate discussions of Gerhard’s output.

Yet before he studied with Schoenberg, Gerhard was a pupil of Granados and Pedrell (the latter commemorated in his Pedrelliana); so it is not really a paradox that long after his years in Vienna and Berlin he continued to write music recognisably in the ‘Spanish nationalist’ tradition – more specifically within the traditions of his native Catalonia. Such colourful, danceable, folk-inflected scores as the 1932 Cantata or the Albada, Interludi i Dansa hardly fit any theory of evolutionary modernism. Yet Gerhard’s enlarged experience enabled him to bring to them and their like a rare compositional discipline, and to open up new resources of organised chromaticism (already explored in the Haiku and Wind Quintet) that broadened the ‘folkloric’ archetype into a music of universal significance. The major compositional statements of this synthesis are the ballet Don Quixote and the opera The Duenna (the most felicitous of whose many marriages is surely its amazingly natural wedding of the Iberian musical vernacular to English prosody), but Gerhard saw no incongruity in producing such relaxed entertainments as Alegrías and Cancionero de Pedrell. All in all, this was an achievement comparable to that of Bartók in Hungary, but effected by different means.

In fact, Gerhard never truly renounced his Catalan heritage, which continued to nourish his flamboyant colour-sense and even provide specific melodic gestures right up to his very last scores. But the Concertos for violin, piano and harpsichord chart a progress away from the more anecdotal aspects of that heritage towards a more flexible and radicalized language. The first major embodiment of that perfected manner is the official First Symphony, one of Gerhard’s most powerful works; and it is consolidated in the following orchestral and chamber scores, such as the Nonet. These works illustrate, to an astonishing degree, the union of post-Schoenbergian serial rigour with freely-evolving, apparently improvisational fantasy: the Debussian ideal of music as ‘endless arabesque’. And even at their most radical and uncompromising, these works are imbued with a Mediterranean warmth and brilliance, a dark vision and dry humour, that speaks of their composer’s essential roots.

Calum MacDonald, May 1991

"A composer needs grace (inspiration), guts, intellect, madness"

"Discovery is nothing. The difficulty is to acquire what we discover."

"There are countless music-lovers the world over who lay no claim to under-standing (in any logical sense) the music they enjoy, and some are amazingly perceptive. Only think of the meagre audiences of cognoscenti that would be left us without that great body of pure amateurs. True, they must be led through the maze of the contemporary scene by an informed elite. But in the last resort their response will also be the ultimate test of that elite."

R.G.