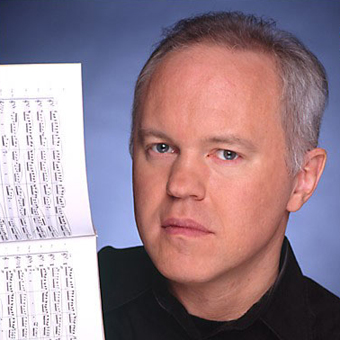

Michael Torke

An introduction to Michael Torke’s music

by Mark Swed

With his two best known pieces, Ecstatic Orange and The Yellow Pages, written in 1985 while still a composition student at Yale, Michael Torke practically defined post-Minimalism, a music in which eclectic young composers utilize the repetitive structures of a previous generation to incorporate musical techniques from both the classical tradition and the contemporary pop world.

Moreover, thanks to their stirring energy and riotous application of glossy instrumental color, The Yellow Pages, written for chamber group, and Ecstatic Orange, Torke’s first orchestral piece, seemed to reflect the optimistic, almost cocky, spirit of the arts of the Eighties. Like Deconstructive architecture, Torke’s music doesn’t hesitate to take the familiar stuff of pop music and break up and reassemble it into a wondrously unpredictable bustle. Like Postmodern literature and painting, Torke lets striking musical imagery grab the senses and carry them along with a rhythmic bravado that has struck many as irresistible.

Surprisingly Torke has done this by employing procedures and approaches dear to composers as far back as the Middle Ages – the enlivening of art music with popular dance music and the evocation of colors through sound – but in ways that made them seem something completely new in music. Partly, that is because however much Torke finds inspiration in pop song, it is a personal inspiration that mostly remains in the background, such as using a Chaka Kahn bassline as the basis for a private ostinato. And his notion of color is equally quirky and individual. Torke has a strong sense of synesthesia, associating different chords or key areas with specific colors; and many of his pieces are named for colors, taking their mood and character from his interpretation of that color.

Unlike many American composers who grow up in a world of popular music, and then feel compelled to expunge those influences when they turn to "serious" composition, Torke, who is also a virtuoso pianist, spent his youth immersed in conventional classical music. He discovered rock and jazz recordings only when he attended the Eastman School of Music, but his enthusiasm for popular music has been something of a mission in his work ever since. In varying degrees, pop elements might affect the structure of a piece, dictate harmonic or melodic materials, or animate the rhythms and pulses of a score. Mainly, however, those pop elements pervade Torke’s work not so much in their overt sound or structure – since the music is exquisitely and often neo-Classically made – than in the more subjective sense of bringing the energy of rock to concert music.

And thanks to such driving energy, popular music being dance music, Torke’s works, both chamber music and orchestral, have strongly appealed to choreographers, and especially to Peter Martins of the New York City Ballet. To date, Martins has choreographed seven of Torke’s compositions (of which four were NYCB commissions), evoking the relationship between Balanchine and Stravinsky in an earlier era of the company’s history.

Stravinskyan is also an adjective regularly applied to Torke’s music, since it shares with Stravinsky restless developments of fragmented themes and an irrepressible rhythmic ingenuity. But it is primarily Torke’s formal procedures that most closely continue a Stravinskyan tradition. In Adjustable Wrench, for instance, a four-bar pop phrase becomes as radically and intricately transformed through unpredictable development as a folk source might in Stravinsky or Bartók.

But while such procedures characterize nearly all of Torke’s work, their application varies considerably in degree from piece to piece. At one extreme, Torke, after including an increasing number of 18th- and 19th-century elements in his music – such as the Beethovenian developmental procedures he so boldly employed in Ash – experimented with outright 18th and 19th-century pastiche in the choral Mass, a dance ritual written for the New York City Ballet, and Bronze, for piano and orchestra.

That, however, proved a short-lived detour, and Torke’s recent return to a more modern, propulsive, pulse-driven style has made the tensions even more dramatic, especially as his harmonic, melodic and developmental language have evolved in complexity. Moreover, he has continued to find new ways of enriching concert music with non-classical techniques. In the recent string quartet, Chalk (for which the composer provides the extraordinary image of "chalky smoke of rosin lifting from he bridges of stringed instruments due to the intensity of the player’s bow strokes"), Torke asks that mechanistic rhythms be treated with sheer physical abandon from the players. Here, by undercutting the classical formality of Minimalist rhythm with the passionate performance style of rock, Torke has refashioned those ever-present conflicts between the classical and romantic into the modern colors and patterns of the late 20th century.

Mark Swed, 1994

(Chief critic of The Los Angeles Times)