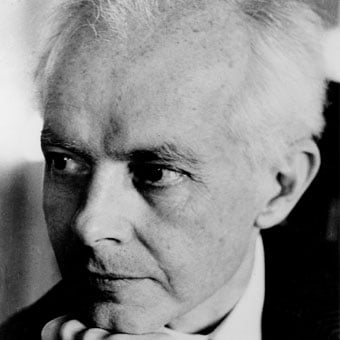

Béla Bartók

An introduction to the music of Béla Bartók

by Malcolm Gillies

Béla Bartók was a Hungarian whose nationality lies at the heart of his musical inspiration and innovation. And it led him to the rich veins of other East European traditions, and to his ultimate cosmopolitanism as a musician and man. But Bartók’s nationality has also been a stumbling block to his acceptance as a musical master of the stature of Johannes Brahms or Igor Stravinsky.

Overshadowed by the musical supremacy of Germany and Austria, any talented Hungarian in Bartók’s day was faced with the dilemma of staying at home, and being considered a merely provincial phenomenon, or leaving for the international ‘hot spots’ of western Europe or north America. The conductor Georg Solti left early. Zoltán Kodály stayed put. Bartók and his colleague Erno Dohnányi dallied – patriotic yet disillusioned – but ultimately they left, but too late to establish worthy new careers abroad. Their musical fates came to hang on the whims of posterity, and the advocacy of others.

Today’s inheritance of Bartók’s repertory is patchy and not always a good reflection of the ultimate quality of his music – or its relevance to the ears of new twenty-first-century audiences. The works we now know best usually started out with early exposure on the international stage, during Bartók’s frequent but fleeting visits abroad in the 1920s and 1930s. Mostly they are instrumental works, usually involving pianos or strings somewhere in the mix. His most popular work over the ages is, interestingly, a small set of six Romanian Folk Dances (1915), available in myriad arrangements from solo piano to full orchestra.

Bartók’s choral and vocal works, by contrast, are neglected, although artistically they lack nothing at all. With original texts in languages such as Hungarian, Romanian or Slovak, they continue to lurk – despite European Union expansion eastwards – behind an iron curtain of language and culture. Yet listen to Village Scenes or the Cantata Profana and you realize how vocal Bartók has its own mastery. And little wonder, given those thousands of folksongs he spent half his life analyzing and categorizing!

Born in 1881 in a provincial Hungarian town (now part of Romania), Bartók soon dedicated himself to the national cause. His early symphonic poem Kossuth (1903), for instance, lamented the abortive Hungarian War of Independence of 1848-49. But Bartók’s unique Hungarianness only began when he realized that this heroic Hungarian lament was nothing but a pastiche of his Germanic inspiration of the moment, Richard Strauss.

Bartók’s real Hungarian innovation was to take the tunes of the swineherd and the peasant girl into the concert hall in all forms of dress and combination. He did that, in part, through arrangements – some disarmingly simple (like his first setting, ‘Red Apple’), some alarmingly complex and dissonant (like his Improvisations of 1920). But he also digested these influences to produce, in his longer and later pieces, a fully integrated, utterly distinctive yet still folkinspired style. We hear that powerful homogenized utterance, for instance, in any of the six string quartets or in the stunning Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta – perhaps his consummate work of the 1930s. So, folk Bartók begat art Bartók.

Unlike Kodály, Bartók ranged very widely in his ethnographic thinking. Within a couple of years of starting to collect folk music he had discovered equally fertile fields among the Romanian and Slovak communities of Old Hungary. Later, he wandered wider still, visiting the Berbers of North Africa and the Turks of Anatolia. Such compositions as the Piano Suite, Dance Suite and Mikrokosmos reflect these non-European inspirations, sometimes with the same glowing intensity heard in works of Arabic influence by the Pole Karol Szymanowski or the Briton Gustav Holst.

Between the wars Bartók gradually became a citizen of the world. Radio, the gramophone and new opportunities for travel helped him to transcend artistic and political boundaries. His years on a League of Nations’ committee in the 1930s also brought out a new purpose of artistic internationalism. Bartók’s Cantata Profana was the first of an intended “Danube trilogy”, and a prelude to the increasingly pan-national style of his ‘golden years’ as a composer: 1934-39. From these pre-War years come so many of the Bartók chamber classics, but also the littleknown three songs From Olden Times for male chorus and

his challenging Violin Concerto No.2.

No self-respecting orchestra can overlook the late-flowering, mellow fruits of Bartók’s years of exile in America: the Concerto for Orchestra and Third Piano Concerto. And for the chamber audience, the Sonata for Solo Violin that Yehudi Menuhin commissioned from Bartók in 1944 remains as breath-taking, beautiful and strong as ever.

With such a strong portfolio of instrumental works for the concert hall, Bartók’s gift for the stage is sometimes overlooked. Yet The Miraculous Mandarin pantomime, written during heady days of influenza pandemic, war surrender and revolution (1918-19), is an unrivalled

masterpiece – truly Bartók’s answer to Igor Stravinsky’s ballet The Rite of Spring and Alban Berg’s opera Wozzeck.

Although Bartók was not a film-music composer of the ilk of Saint-Saëns, Korngold or Shostakovich, the percussive and rhythmic qualities of his music adapt superbly to stage and screen. It is not by chance that so many of his works, or individual movements, include the word ‘dance’ in their titles. Stanley Kubrick’s horror movie The Shining (1980) three times returns to the eerie third movement of Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936) to build the film’s incredible tension. Other music with superb filmic potential includes the supernatural moments of The Miraculous Mandarin (1918-19), and the rich, Finno-ugric sounds of Bartók’s unaccompanied male choruses.

Bartók died within weeks of the end of the Second World War. As soon as he was dead, it seems, the popularity of his music took off, at least in the West. While newly Communist Hungary suppressed his more ‘abstract’ works for some years, the diaspora of great Hungarian musicians – conductors like Reiner and Doráti, the violinists Székely and Szigeti, and such pianists as Kentner and Sándor – promoted his works across the world more effectively than Bartók himself could ever have conceived. The new LP era pushed Bartók, for several decades, into lists of the top halfdozen best-selling twentieth-century composers. The six string quartets led at the quality end of the classical market, while works like Romanian Folk Dances were happily positioned at the more popular end. Among composers acknowledging a direct influence from Bartók are Messiaen, Ginastera, Copland, Crumb, Lutoslawski, and Benjamin Britten. As with many post-War Hungarians György Ligeti showed strong Bartókian influence in his early works of the 1950s but also in his later works, from the 1980s.

Now 60 years after his death, Bartók’s reputation as a musical genius is undiminished. However, history’s tendency to reduce the richness of diversity into a few sanctioned examples – the inner canon – needs to be resisted. Bartók means more than a small cluster of quartets, orchestral pieces and piano works. To renew audiences, continually challenge performers, and provide the simple tonic of the less familiar, each generation needs to find its own answers to the essential qualities of his greatness. In short, to confront Bartók afresh.

© Malcolm Gillies, 2007