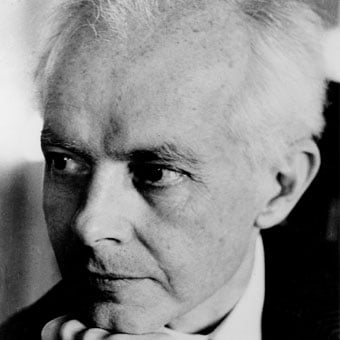

Béla Bartók

d. 26 September 1945, New York

Béla Bartók was born in the Hungarian town of Nagyszentmiklós (now Sînnicolau Mare in Romania) on 25 March 1881, and received his first instruction in music from his mother, a very capable pianist; his father, the headmaster of a local school, was also musical. After his family moved to Pressburg (now Bratislava in Slovakia) in 1894, he took lessons from László Erkel, son of Ferenc Erkel, Hungary’s first important operatic composer, and in 1899 he became a student at the Royal Academy of Music in Budapest, graduating in 1903. His teachers there were János Koessler, a friend of Brahms, for composition and István Thoman for piano. Bartók, who had given his first public concert at the age of eleven, now began to establish a reputation as a fine pianist that spread well beyond Hungary’s borders, and he was soon drawn into teaching: in 1907 he replaced Thoman as professor of piano in the Academy.

Béla Bartók’s earliest compositions offer a blend of late Romanticism and nationalist elements, formed under the influences of Wagner, Brahms, Liszt and Strauss, and resulting in works such as Kossuth, an expansive symphonic poem written when he was 23. Around 1905 his friend and fellow-composer Zoltán Kodály directed his attention to Hungarian folk music and, coupled with his discovery of the music of Debussy, Bartók’s musical language changed dramatically: it acquired greater focus and purpose – though initially it remained very rich, as his opera Duke Bluebeard’s Castle (1911) and ballet The Wooden Prince (1917) demonstrate. But as he absorbed more and more of the spirit of Hungarian folk songs and dances, his own music grew tighter, more concentrated, chromatic and dissonant – and although a sense of key is sometimes lost in individual passages, Bartók never espoused atonality as a compositional technique.

His interest is folk music was not merely passive: Bartók was an assiduous ethnomusicologist, his first systematic collecting trips in Hungary being undertaken with Kodály, and in 1906 they published a volume of the songs they had collected. Thereafter Bartók’s involvement grew deeper and his scope wider, encompassing a number of ethnic traditions both near at hand and further afield: Transylvanian, Romanian, North African and others.

In the 1920s and ’30s Bartók’s international fame spread, and he toured widely, both as pianist (usually in his own works) and as a respected composer. Works like the Dance Suite for orchestra (1923), the Cantata profana (1934) and the Divertimento for strings (1939), commissioned by Paul Sacher, maintained his high profile; indeed, he earned some notoriety when the Nazis banned his ballet The Miraculous Mandarin (1918–19) because of its sexually explicit plot. He continued to teach at the Academy of Music until his resignation in 1934, devoting much of his free time thereafter to his ethnomusicological research.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, and despite his deep attachment to his homeland, life in Hungary became intolerable and Bartók and his second wife, Ditta Pásztory, emigrated to the United States. Here his material conditions worsened considerably, despite initial promise: although he obtained a post at Columbia University and was able to pursue his folk-music studies, his concert engagements become very much rarer, and he received few commissions. Koussevitzky’s request for a Concerto for Orchestra (1943) was therefore particularly important, bringing him much-needed income. Bartók’s health was now failing, but he was nonetheless able virtually to complete his Third Piano Concerto and sketch out a Viola Concerto before his death from polycythemia (a form of leukemia) on 26 September 1945.

Béla Bartók is published by Boosey & Hawkes.

This biography can be reproduced free of charge in concert programmes with the following credit: Reprinted by kind permission of Boosey & Hawkes