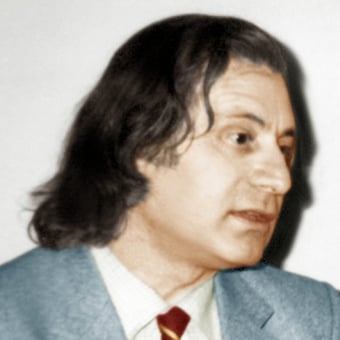

Alfred Schnittke

An Introduction to Schnittke’s music

by Gerard McBurney

Alfred Schnittke belonged to a remarkably rich generation of Soviet composers, those born in the 1930s, who as children lived through violent political repression and the deprivations of World War 2, but who came to personal and artistic maturity at a very different time, between the mid-1950s and the mid-1960s, during the relatively freer post-Stalinist period known as ‘the Thaw’. In those days, the First Secretary of the Communist Party (the effective ruler of the USSR, and Stalin’s successor) was Nikita Khrushchev, a complex and paradoxical figure who, despite frequent illiberal outbursts, set in motion a loosening of Soviet cultural life, including the release and publication of previously hidden works of art (literature, music, films), greater contact with Western and other foreign influences, and the opportunity for new kinds of experimentation and innovation from within Russian artistic and intellectual circles. As Schnittke himself later liked to say, with characteristic understatement, ‘this was a time of possibilities’.

Naturally, it was tricky, not only politically but creatively and personally, for young artists in that situation to balance their responses to all the new and contradictory influences that swirled around them. Some of Schnittke’s generation, for example, remade themselves as epigonic versions of Schoenberg and Webern, John Cage or Stockhausen. Others turned to deep and long-repressed nationalist and traditionalist roots, especially those associated with Orthodox Christianity.

Schnittke’s creative journey had elements of these various approaches, but was distinct. In part, this was a matter of his background. His father was of Russian-Jewish extraction but was born and brought up in Frankfurt, before the family returned to the USSR in 1927. He was therefore – in Soviet terms – a ‘foreigner’. By contrast, the composer’s mother came from the old German minority communities established in Russia along the Volga River by the Empress Catherine the Great in the 18th century. The language in the family home was German (tinged, as the composer observed with a wry smile, by forgotten idioms of long ago). And there was a presence of religion, a tricky matter in those days: Schnittke’s maternal grandmother, who played a large part in his upbringing, had preserved her old Catholic faith and her beliefs made a strong impression on the boy. And then there was a moment just after the end of the war, when Schnittke’s father took a job as a journalist in Soviet-occupied Vienna, and the family found themselves living in a German-speaking city, the home of the classical composers and many of their successors, and a place with a musical life quite unlike anything in the USSR. This was an experience unimaginable to most young Soviets of Schnittke’s age.

All these elements combined to give him a sense he often mentioned of feeling an outsider in the Soviet Russian-speaking world in which he lived, with its heavy, repressive and often racialised orthodoxies. As he quietly observed in later life, “I have spent many years looking for a home”.

Predictably, Schnittke’s earliest compositions sound ‘Soviet’ enough, written in the then available musical language, a mixture of à la russe and Socialist Realism, spiced with more daring elements from Prokofieff and Shostakovich. Soon, however, the young composer began to hear whispers of other worlds. In 1956, the Warsaw Autumn festival was founded, and recordings and broadcasts of its concerts filtered through to Soviet ears, with new works by exciting young Polish contemporaries – Lutoslawski, Górecki, Penderecki and the rest – and within a few seasons the music of younger ‘Western’ composers of the then so-called ‘avant-garde’. Occasionally, exotic visitors arrived in Moscow and Leningrad, sometimes with scores or recordings, sometimes performing: Glenn Gould in 1957, with news of Schoenberg, Berg, Webern and others; Luigi Nono, with armfuls of pieces by Darmstadt colleagues; Boulez with the BBC Symphony Orchestra; and, symbolically most important, Stravinsky’s return to his native land in 1962.

Under this deluge of new impressions, Schnittke’s interests naturally began to change, and the music of his early maturity gives a vivid sense of a young man, passionate, hungry, eager to try as many approaches as possible. A stream of devices and gambits popular at that period appeared in various forms and combinations in his music: 12-note-rows, neo-tonal gestures, elements of the ‘total serialism’ that not long before had been all the rage, heterophony in the manner of Polish and Hungarian composers, quotation, collage, kitsch and parody, religious symbolism, special effects of instrumentation and strange instruments, modal devices and harmonic filters, tape-recorders, and even electronic music (courtesy of the ASM studio in Moscow).

The most impressive aspect of Schnittke’s creative personality at this time is that for all the noise and clutter of his kaleidoscopic enthusiasms, the actual pieces sound remarkably consistent. The young composer was already, it seemed, in possession of a balanced inner voice which meant that whatever he took from outside, he quickly transformed into something personal.

Partly this was a matter of technical fluency. By now, like many Soviet composers, he was earning the better part of his living in the film industry, writing scores for every kind of movie. This taught him speed and practicality, and gave him the chance to experiment in different ways. Soviet cinema was not policed by the same authorities who controlled the Composers’ Union, so there was less political and ideological oversight of the music. Producers and directors seem to have been principally concerned that the scores they commissioned should be dramatically effective and atmospheric.

Schnittke’s fascination with his German roots certainly played a part in centring his vision. He devoured German literature – Thomas Mann, Kafka and others – but also German music; and the sound and, perhaps more importantly, the core sound-values of German and especially Viennese music deeply influenced him: from Beethoven, through Schumann, Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler to Schoenberg, Berg and Webern. This tradition, he noted later, quickly came to seem to him a kind of ‘home’, very different from the Russo-Soviet fare dominant in the Moscow concert life he knew.

At the same time, much in Russian and Soviet music was crucial to his development. Like most young musicians educated in the USSR, he was deeply influenced by the various modal and symbolic traditions of explaining and teaching music, traditions stretching back to 19th century Russia and figures like Glinka, Moussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov. And he was profoundly and uneasily affected by Shostakovich, the overpowering voice in Soviet music in those days, but to the young Schnittke – as to many of his contemporaries – an ambiguous figure (aesthetically and politically): to be respected and admired, but also to be treated with suspicion, resistance and sometimes outright hostility.

Schnittke’s early professional life culminated with the composition of one of his greatest achievements, his First Symphony of 1972. This astonishing piece brings together everything he had learned – and indeed composed – thus far into a gigantic circus-show of film music and concert music, early music and new music, the trivial and vulgar with the grandiose, the borrowed and the stolen with the completely new, comedy and absurdity side by side with tragedy. In particular, this score contains elements of theatre and of freedom, including a substantial passage for jazz musicians where they are free to improvise whatever they want, while, miraculously, at the same time the music is held firmly together by a hidden, almost numinous inner architectural structure.

Inevitably, this symphony caused a scandal when it was first performed in 1974 – discreetly out of the way of Moscow audiences and foreign attention, in the closed city of Gorky (nowadays returned to its original name, Nizhny Novgorod). The nomenklatura of the Composers’ Union reacted with special anger and hostility, their authority having been called into question by the very existence of such a piece. But for younger Soviet composers, many of whom travelled long distances from other parts of the USSR to be present at the première, this music was like a call to arms. As the late Viktor Suslin put it, referring to Solzhenitsyn’s famous novel:

“You must understand that for our generation, Schnittke’s symphony was like The Gulag Archipelago in music.”

For Schnittke himself, this piece, while unquestionably important, represented as much the end of an era, a summing up of everything achieved so far, as any kind of breakthrough into something new. His mind was already moving on to other thoughts. And one aspect of that was his increasingly close connection to certain key performers. Here, a critical role was played by the violinist Gidon Kremer. After Kremer’s first appearance in the West in 1970, his international reputation was quickly established as one of the great violinists of the age. And as he travelled the world, he was determined to take the music of his favourite living Soviet composers with him.

As a consequence of Kremer’s pioneering work, Schnittke and his contemporaries now found themselves increasingly writing with particular performers in mind: not only Kremer, but Natalia Gutman and her husband Oleg Kagan, and – a little later – Mstislav Rostropovich, not to mention other powerful figures, and – more and more – different orchestras and conductors around the world and especially in what was still in those days called ‘The West’. For Schnittke this meant that the power of his music, as it quickly gathered a wider audience, was closely linked to the people who played it, and, given who those people were, beyond them to the wider rhetoric of international cultural politics in the closing years of the Cold War. Schnittke’s music, in other words, became in itself a form of political drama on the international stage, something which happened also to a number of his Soviet contemporaries, including – as well as composers - writers, theatre-makers and film-makers.

In 1985 Schnittke’s life was changed by a stroke which nearly killed him, followed by other catastrophic changes to his health.

The effect of this disaster on the sound of his music was something Schnittke himself found fascinating and often talked about with his friends. As he saw it, his brush – and, subsequently, several more brushes – with death had forced him to think about music in a new way. Living most of the time by now in Hamburg, Germany, and widely performed around the world, he was composing with ever greater fluency, pouring out symphonies, concertos, operas, ballets and a mass of chamber music, right up to his death in 1998. But the language of his music had changed.

He himself put it like this:

Earlier in my life, I had to prepare carefully to write music, to lay the foundations, to work out the techniques I was going to use. Now I have discovered since my illness that my task is simply to listen as intently as possible to what I hear. And what I hear I hear with a clarity I didn’t possess before. And what I hear is what I write.

Listening to his often extremely moving last works, one has the impression of a man at the end of a long journey, often content to let his music distil to a single wandering line, even in a work for full orchestra, allowing single instruments to float almost like gossamer in the air, or homing in on a single idea obsessively repeated. For Schnittke it was a question of letting the music do the work, of not trying to direct it down paths it didn’t want to go along.

Perhaps this is why so much of the music of his final years is filled with spaces and with silences. As he himself said of one of his later symphonies:

What is most important to me in this piece… are the pauses.

© Gerard McBurney, 2022

(Composer, orchestrator, writer, broadcaster, deviser, reconstructor of lost and forgotten works by Shostakovich.)